Kind of a cool extension to the AVX instructions discussed in lectures are the AMX instructions (which target an accelerator for matrix operations on the chip) that are supposed to be usable in the next generation of Intel Xeon processors (https://en.wikichip.org/wiki/x86/amx).

What limits the number of ALUs you can add? ALUs seem a little like free execution to me, what prevents you from just adding a lot more or why would that not be a good idea?

How do chip designers make these sorts of decisions, such as how many ALUs? Do they simulate common workloads and programs? Do they ever work together with compiler writers to collaborate on a new feature?

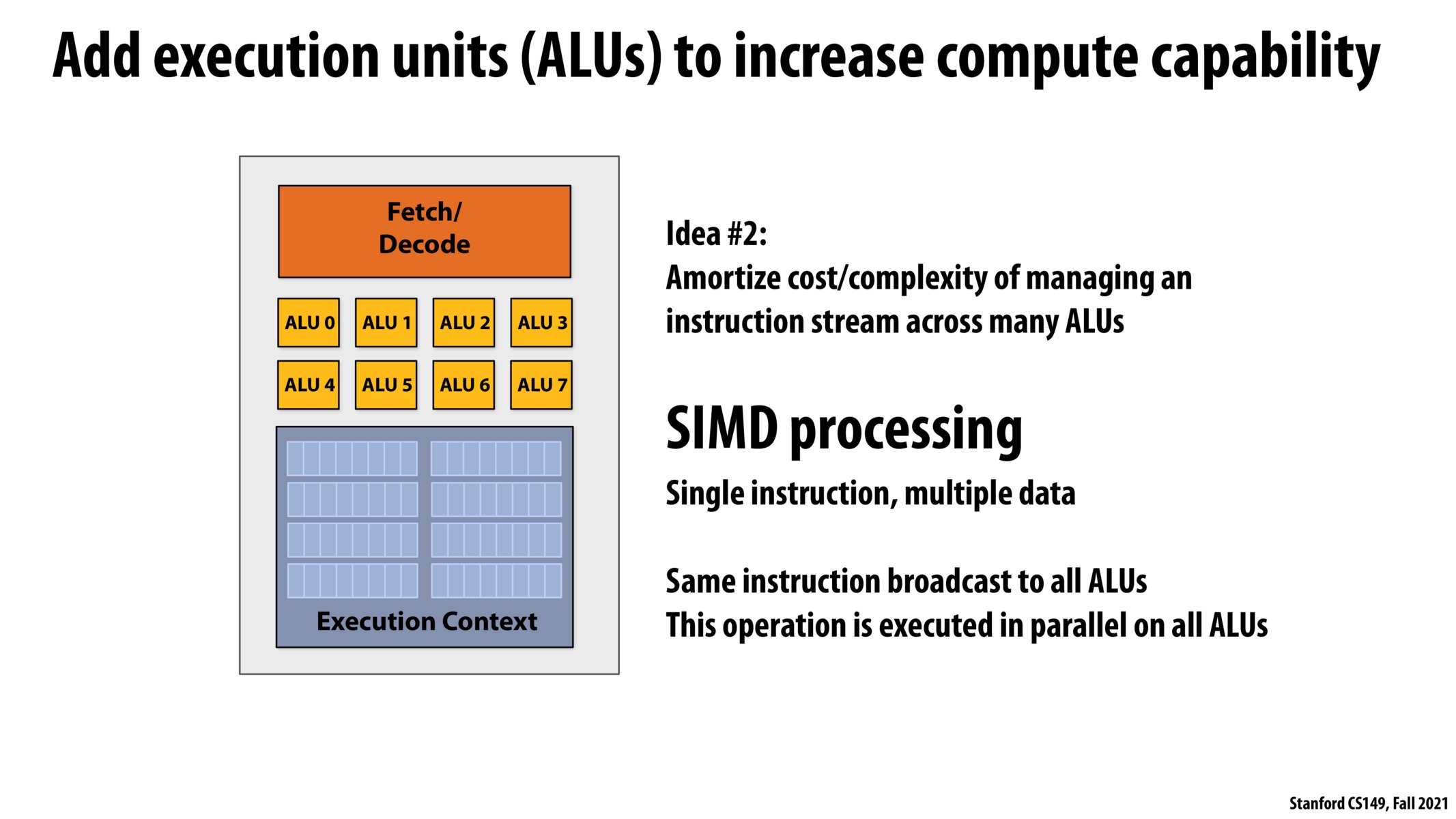

Does SIMD execute one instruction on multiple ALUs in one clock cycle?

Are certain ALUs specialized to handle certain types of data? Or all the ALUs identical?

@gohan2021 from what I understood from lecture, that is the case. I am sure someone else will come along and correct me if it is not though. As long as all of the data in the ALU's have the same instruction being performed on them, this is the case. I think slide 38 does a good job of putting this into a visual.

If a programmer never uses the full capacity of all the ALU's in a single instruction stream, isnt it wasteful?

From my understanding of this concept, yes. Perhaps the number of ALUs used is dependent on the application (more useful for some rather then others).

@beste. I wanted to clarify: the utilization of the ALUs is a property of the application. Applications with significant instruction stream divergence won't be able to efficiently utilize wide SIMD execution. However, the number of ALUs is determined by the processor's design, and is independent of software.

Please log in to leave a comment.

I wonder if the increased number of ALUs in one core requires an increased execution context size to store data compared to a core with a single ALU.