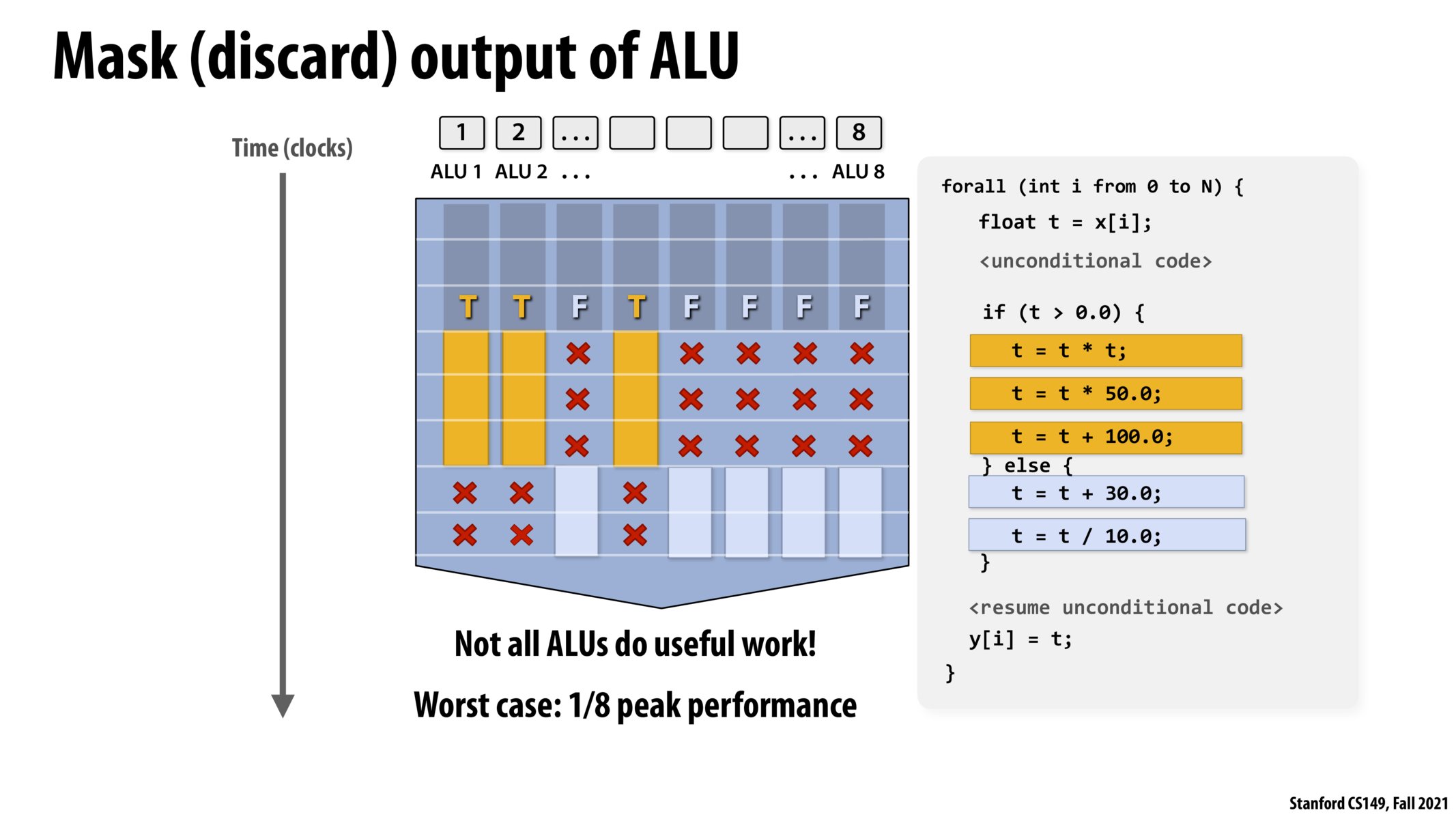

Adding on to @bigchungus' question, I'm a bit unclear on how we are defining peak performance in the context of these SIMD operations.

@rahulahoop From what i understand, the peak performance in the context of these SIMD operations is using all 8 ALUs in one clock cycle. The worst case is defined as only 1 of the ALU's being used. For example, if the program only performed t = t*t in the first "if statement", then it would only use one ALU in one clock cycle, which is 8x worse than peak performance.

how is this entire process (execution of both branches of the conditional, masking) beneficial over conditional evaluation?

@bryan If we did conditional execution, we would have to evaluate the conditional and do either the orange or blue section 8 different times, all in sequence. The different ALUs in this processor must be doing the same operation together, so they can't perform different executions on each data.

Is there a case where one branch may be impossible to run? i.e.

for ... {

if (x = 1) { x = x - 1 } else { x = x/(x-1) } }

In this case, if we run both branches through the if, there will be divide by zeros for some or you can imagine accessing an out of index. Guess the ALU might have some specifics we don't know about when handling these operations?

@michzrrr I imagine this depends on processor specifics, but here are my guesses:

1) if there is a divide by 0, the SIMD instruction may output some junk value which ends up being discarded (like NaN for floats). Perhaps any error which would be thrown is evaluated once those values are actually used.

2) Accessing memory is probably not possible as a SIMD instruction (it's more often for things like addition and multiplication), but if it were then we could use the same strategy

I wonder of there is any speedup from simd instructions in terms of memory. For example, does fetching memory as larger blocks for simd instructions reduce memory delays more compared to single register instructions.

@bigchungus @rahulahoop I have couple examples on slide 40 that might be helpful. I plugged in some numbers to calculate how we get 1/8 of peak performance.

@bigchungus @rahulaloop I think the important thing here is that different branches of execution can take different numbers of cycles. If we imagine if A else B, and A and B each take the same number N cycles, then we have at worst a 2x slowdown: rather than being able to compute 8 inputs in N cycles (if we were able to do all computation at once) we compute 8 inputs in 2N cycles -- N cycles for the A cases and N cycles for the B cases. Note that it doesn't matter how many of the 8 inputs are true versus false. If it's split 4-4 that's the same amount of time as if it's split 7-1.

The biggest thing that cleared this up for me (because I was confused at first too) is that the two branches can require different number of cycles and that's why we can get up to 8x worse. Here's a short example similar to @schaganty's from slide 40. Say A takes 1000 cycles and B takes 1 cycle. Now, imagine we have 8 inputs, 1 of which requires A and 7 of which requires B. Sequential computation takes (10001 + 17)=1007 cycles so our "best case" hope for parallel computation with 8 lanes is 1007/8 cycles. But in actuality we will use 1000 cycles on case A for the first input, then 1 cycle to do all of inputs 2,3,4,5,6,7,8. This is 1001 cycles total, which is almost 8x worse than 1007/8.

@pinkpanther that was super helpful, thanks!

Please log in to leave a comment.

I'm still confused by this claim of 8x slowdown in the worst case, specifically what we're measuring performance relative to.

Consider

if (i % 8 == 0) { t = t + 1; } else { t = t + 2; }Clearly only 1 out of the 8 entries will be TRUE. However, this snippet takes only two clock cycles to compute, one cycle for each branch condition. So how is this an 8x slowdown?