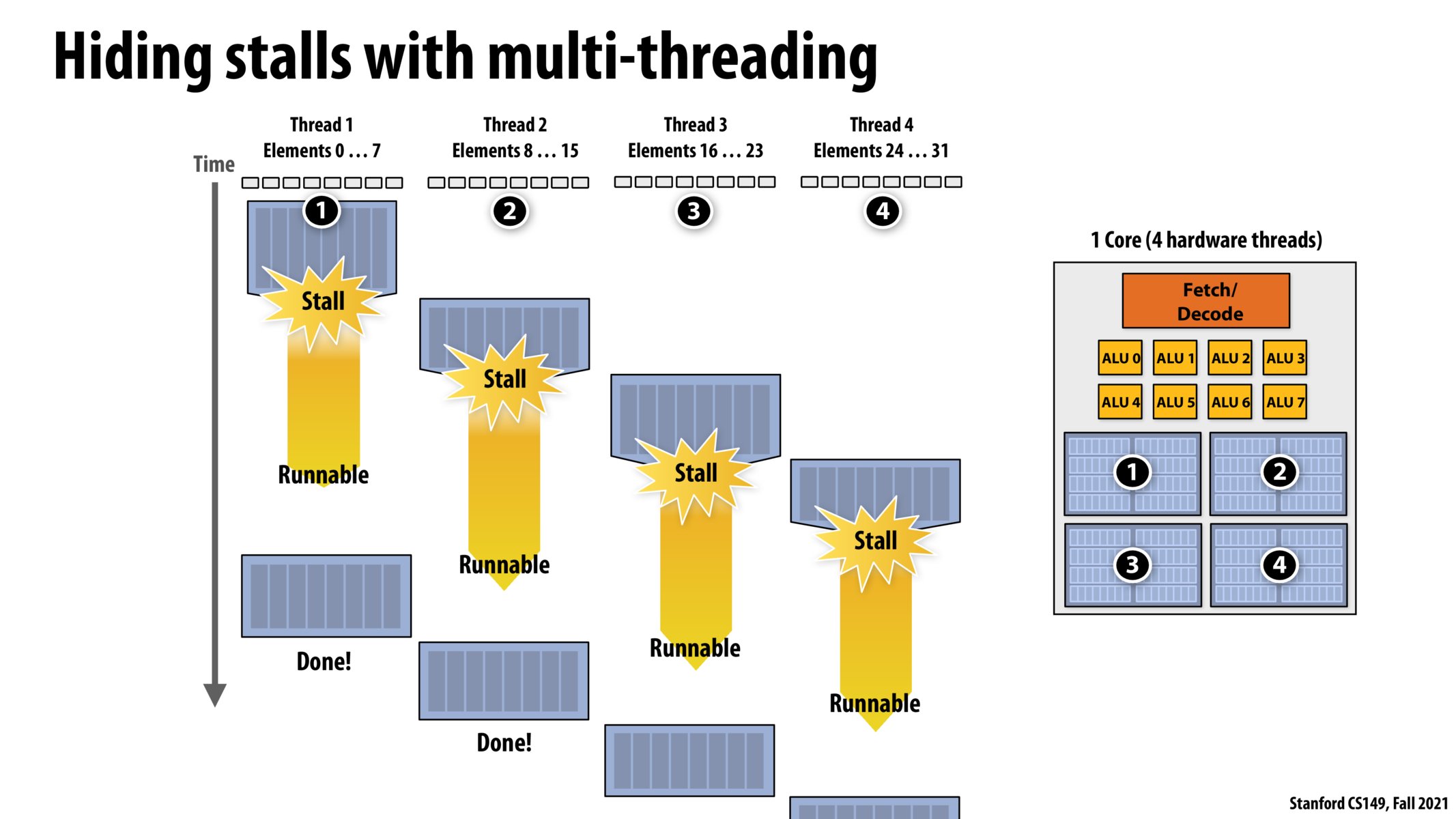

That is correct. (More on this slide.)

What happens if we have, say, 6 threads running concurrently on this core since there are only 4 execution contexts here? Is there some sort of stash/pop happening on the execution contexts?

@potato. The situation you propose is impossible. This core only supports 4 hardware threads. Only 4 threads can run concurrently on it.

If a compute, like my laptop, has many active software threads across many applications, it is the responsibility of software (specifically, the OS) to make decisions about which four threads it wants to make the core aware of. However, the KEY POINT HERE is that from the perspective of the processor core, there are only four hardware threads that it is responsible for running.

Just to check my understanding of the difference between hardware and software context switching: suppose there are 8 threads and 0 - 3 are currently schedule on the core. Hardware context switching switches among 0 - 3 and decides which one to run, while software context switching may switch from 0 - 3 to 4 -7 to be scheduled on this core. Does this sound correct or I may have missed something?

To echo on jaez's question, when does hardware context switching step in if the OS can already decide which threads are currently running on the cores? What are the advantages / disadvantages of hardware context switching compared to software?

@jaez. Your understanding is correct. To re-state in different words.

Let's assume an application creates eight threads. (Or a computer has 8 processes running that each have one thread, etc.). Either way the OS has eight threads that it needs to run on the processor.

Now we also have a processor that can simultaneously interleave execution of four threads. (it has execution contexts for four threads.) At all times, it's the OS's responsibility to choice which four of the eight total threads are "live" on the processor. In other words, those threads are the threads whose state is stored in the processor's execution contexts. The OS can adjust this mapping whenever it wants, but restoring the state of a thread onto a processor execution context is typically a heavy operation required hundreds of thousands of clock cycles -- so the OS is only going to do this a few times a second.

In contrast to the high cost of changing what four software threads are on the processor, the multi-threaded processor is going to be making decisions EACH CLOCK CYCLE about which of those four threads it's actually going to fetch/execute instructions from.

Watching this part of the lecture I was wondering if this explained the difference between the normal Linux kernel and the "Real-time kernel" that we sometimes have to use in robotics. Do normal kernels designate some threads as so high of priority that as soon as they are finished stalling, the core returns to them, regardless of whether other threads have stalled? Or is that what defines real-time kernels?

It is mentioned in the lecture that processor is responsible for switching between these hardware threads to hide stalls. But what if there are still stalls given computation time is very short and memory access is slow, and in this scenario, will OS kicks in to do a context switch and let processor continue running other threads (except these 4 which are still waiting for memory access) to keep full utilization?

I understand a stall could potentially represent that thread waiting on an operation like a load from memory, but are there any other reasons a stall would occur? I am assuming there are other operations which may take longer than a single clock cycle like a load from memory does.

I see how we are taking advantage of 100% utilization of the core when it comes to making sure the core isn't ever sitting around "waiting", but it seems that this system would basically make every individual thread complete slower in time on an absolute scale. Is there some sort of mechanism where threads are prioritized and what are the metrics that are considered when the scheduler picks a thread to continue running when multiple threads are available to run? Also, can this be done on cores that only have one dedicated hardware thread or does the core have to have N hardware threads physically in the chip?

@tigerpanda -- great question. A stall can occur whenever the next instruction depends on the result of a previous instruction, and that instruction is not complete yet. While memory access instructions are the canonical examples of high latency instructions, all instructions have latency. Another example is a stall due to prior arithmetic instruction that may take a number of cycles to complete. All instructions have latency, in particular since the execution of instructions in modern processors is pipelined.

Please log in to leave a comment.

It looks like thread 1 could have resumed earlier but the core was switched to starting thread 4 at that time. So from the perspective of a single thread, we lose out on latency? I.e. multithreading sacrifices individual latency for collective throughput?