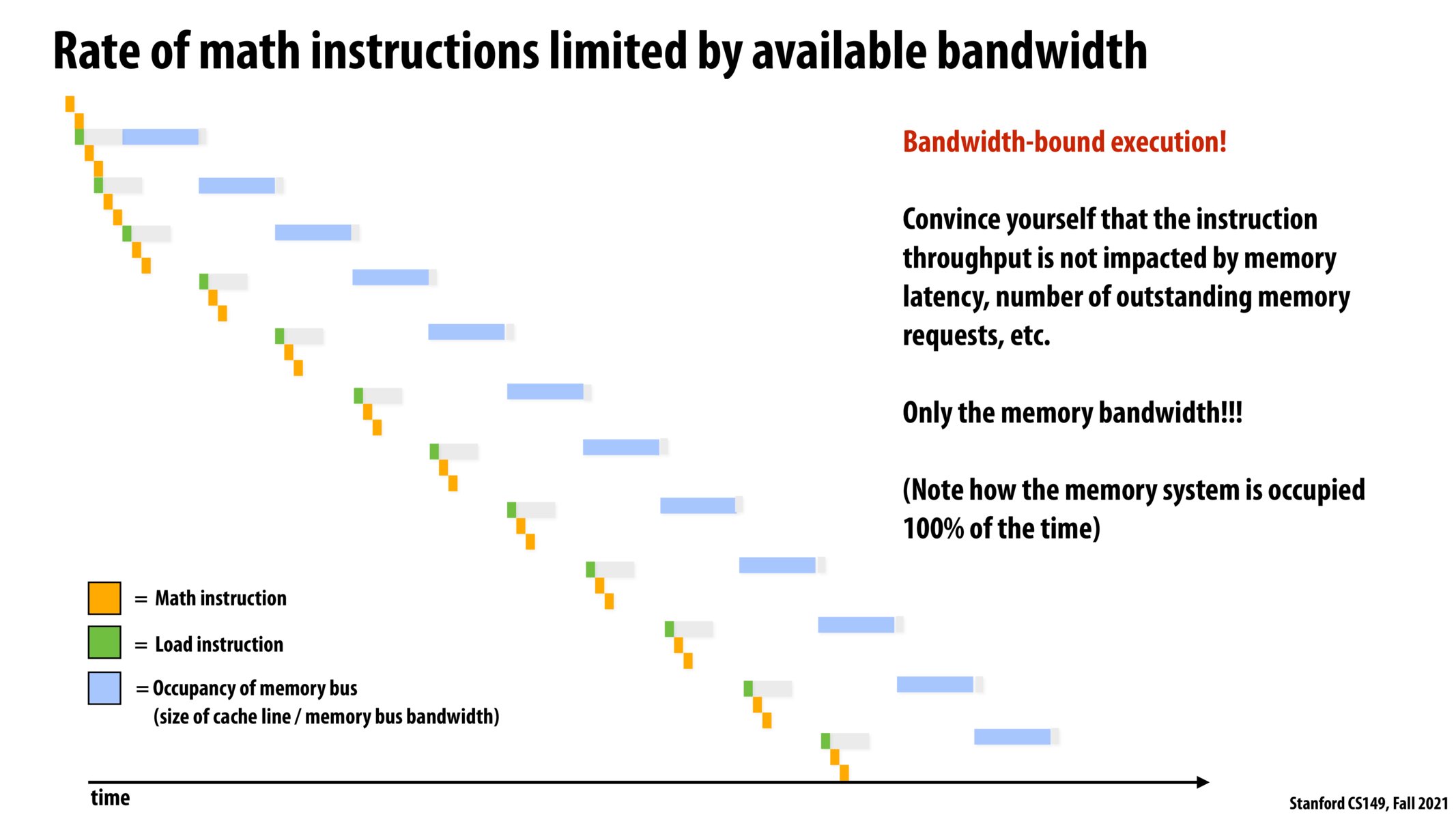

I think it's easier to see this on the previous slide. What's happening is we have instructions run in the sequence "add, add, load, add, add, load, ...". The # of cycles to load and the size of the memory bus is such that we can only issue 3 load instructions before we must wait (until the memory bus has finishes with one of the other load instructions) to issue another load instruction. We can't issue another load instruction, because the memory bus has no bandwidth to handle it. If we allow unlimited outstanding memory request (and the memory bus has unlimited bandwidth -- this is unrealistic as you probably know), then you are right, there would be no stall because we can just run the next load instruction. I don't know enough details about the hardware implementation to answer this well, but you can imagine that when you issue a load instruction it does not get sent into a void. Something must know the instruction was issued and keep track of that etc., and I think that is probably all abstracted into the memory system here.

So if you look at the last slide, the "stall" happens when the next instruction to run is "load" but the memory bus is filled up --> we stall until the first load instruction finishes.

@kv1, thanks for the detailed response. I think we can't issue another load instruction seems mainly due to limited number of outstanding memory requests. I know that blue bar can only be processed after previous blue bar completes, but we can still issue LD requests if the system allows more number of outstanding requests so that processor won't stall and instruction throughput can increase. I am aware that it is unrealistic to have unlimited outstanding memory requests, I just want to point out that if we increase it, instruction throughput will also increase. This program is also bounded by number of outstanding memory requests.

@yt1118 and @kv1. Good discussion and I agree with almost everything above.

However, I would not say that the program is bounded by the number of outstanding requests, only bandwidth. Consider the case where the program is very long running and essentially repeats the pattern above many times. Now convince yourself that regardless of the number of outstanding memory requests allows, as long as that number is FINITE, the system's instruction throughput in steady state will be limited only y memory bandwidth.

It is true that the system's instruction throughput is higher in the initial startup phase when the memory request queue is not full (but filling up), and that a longer memory request queue means that this start up phase is longer than it would be if the queue was shorter. However, we're talking steady state here, and so once the queue fills, the rate items are processed from the queue depends only on the bandwidth of the system, not the length of the queue.

To bring back our laundry analogy... if the washer is much faster than the dryer, the rate that you get loads of laundry completely done is determined completely by the speed of the dryer, not the size of the pile of clothes building up between the washer and the dryer.

@kayvonf, thanks for your explanation. This makes much more senses to me now.

A quick clarification question - where does memory latency come in this diagram? If the latency here means the latency of loading data from memory, wouldn't reducing latency also increase the throughput here (so the blue bar will also be shorter)?

@leopan, memory latency is the grey bar. The blue bar represents memory bandwidth.

To be more accurate, memory latency includes the grey bar. memory latency = grey bar + intervals between grey and blue bars + blue bar.

Just to be 100% precise. The latency of the memory operation is the total time between the start of the operation and the completion of the operation. That's the time between the LD instruction (green) and the completion of the memory load (the end of the little gray bar after blue bar).

You might ask what might this entail... well... for a LD of data at address X to register R0...

- Executing the LD instruction.

- Check the processor's L1 cache for X.

- Checking the processor's L2 cache for X.

- Checking the processor's L3 cache for X.

- Enqueing the memory request in the memory request queue

- Time spend waiting in the memory request queue

- Sending the memory request to memory

- Memory retrieving the data at address X.

- Transferring the data over the memory bus to the processor (blue bar)

- Storing the data in the L3 cache

- Moving a copy of the data to the L2 cache

- Moving a copy of the data to the L1 cache.

- Moving a copy of the data to the designated target register R0.

A real diagram would show all those steps in the process of accessing memory. In the diagram above, I drew the blue bar (time spend transferring data from memory back to the processor), and I illustrated a gray bar signifying some of the early steps above. The region between the gray bar and the start of the blue could be colored in, and that would be time spent waiting in the memory request queue.

That makes a lot of sense. So I guess despite increasing the memory bandwidth could reduce the memory memory latency (the blue bar becomes shorter), there are other ways to reduce the latency that won't affect the "blue bar" here (by shortening the time spent in all the other steps), and hence memory latency is NOT impacting the throughput here. In the end the bounding factor it's still the memory bandwidth (blue bar). Thank you for the explanation!

What is memory bandwidth?

Please log in to leave a comment.

I am still not sure about why the instruction throughput is not impacted by the number of outstanding memory requests. If we allow unlimited outstanding memory requests, there would be no processor stall to the fourth and following LD requests, right?