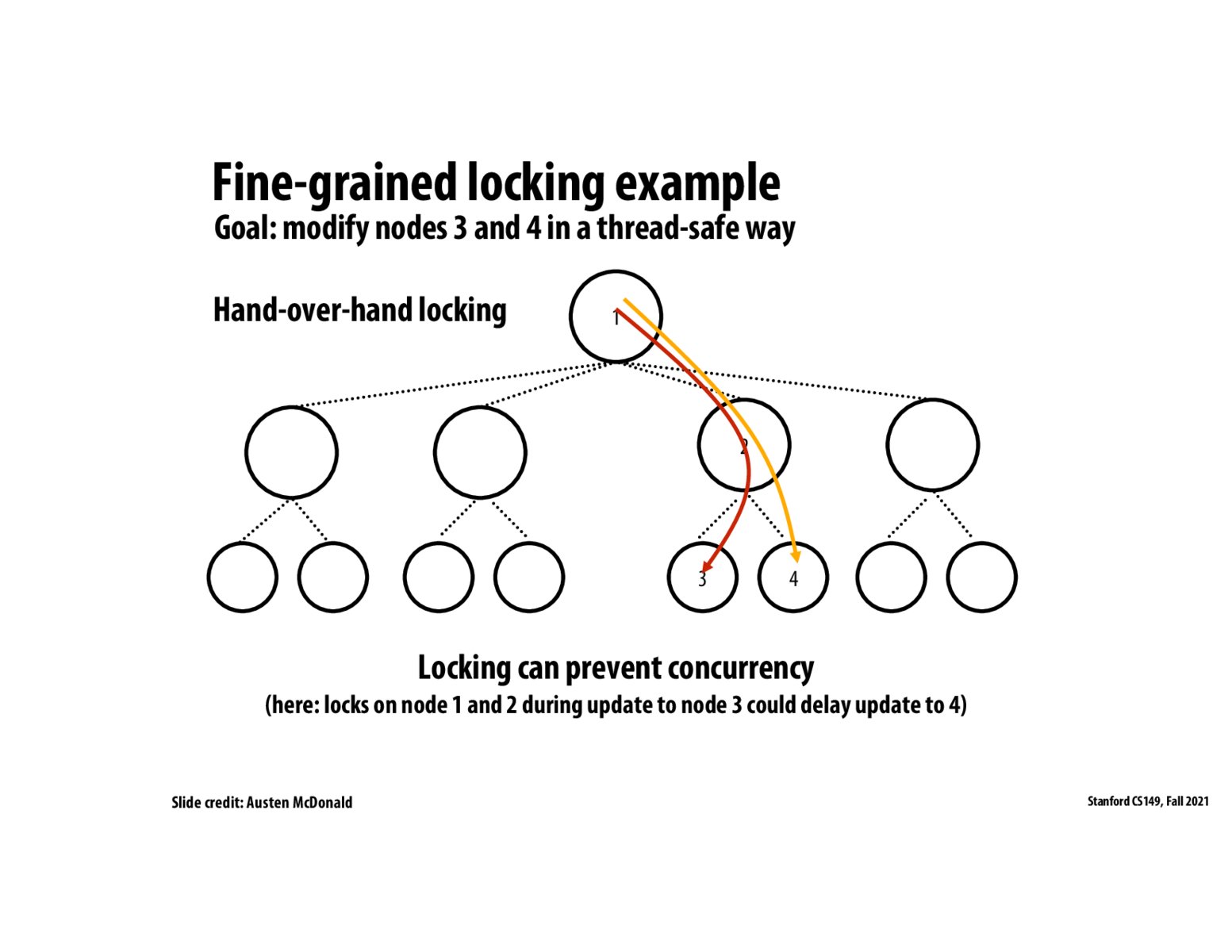

Adding to the above comment, from lecture, holding a lock on a tree node blocks all future threads from operating on all child nodes of the tree. On the other hand, in a transactional system, if the thread locking a node N is not actually modifying it, the other threads can shoot through.

This slide is a little confusing to me. If one thread needs to lock nodes 1 and 2 to update node 3, doesn't this mean that nothing else in this tree could be updated because node 1 is the root of the tree and there is a lock on it? How is this fine-grained locking then?

@tennis_player I assume that the slides means that there will be delays to update node 4 since it needs to wait for locks for node 1 and 2 to be released. Assume T1 wants to update node 3, and T2 wants to update node 4. T1 acquires the locks for 1->2->3 hand-over-hand, and T2 needs to wait until T1 releases locks for 1->2 before it can acquire lock for 4. In contrast with memory transactions, both threads can traverse 1 and 2 at the same time.

A conflict occurs when 2 threads access the same data and at least one of them is a write. Note that this covers both read-write and write-write conflicts. In this example, there are no such conflicts: nodes 1 and 2 are just being read by both threads, and the nodes that are being written to are different for the 2 threads. This is why the 2 threads can work in parallel in a transactional system.

Please log in to leave a comment.

This slide demonstrates the benefit of memory transaction over fine grained locking for this application. In the case of fine grained locking, to modify node 3, nodes 1 and 2 would be locked and thus another thread that has to modify node 4 would need to wait on thread 1 to unlock nodes 1 and 2. With memory transactions, and observing that modifying nodes 3 and 4 has no conflicts the 2 threads can work in parallel.