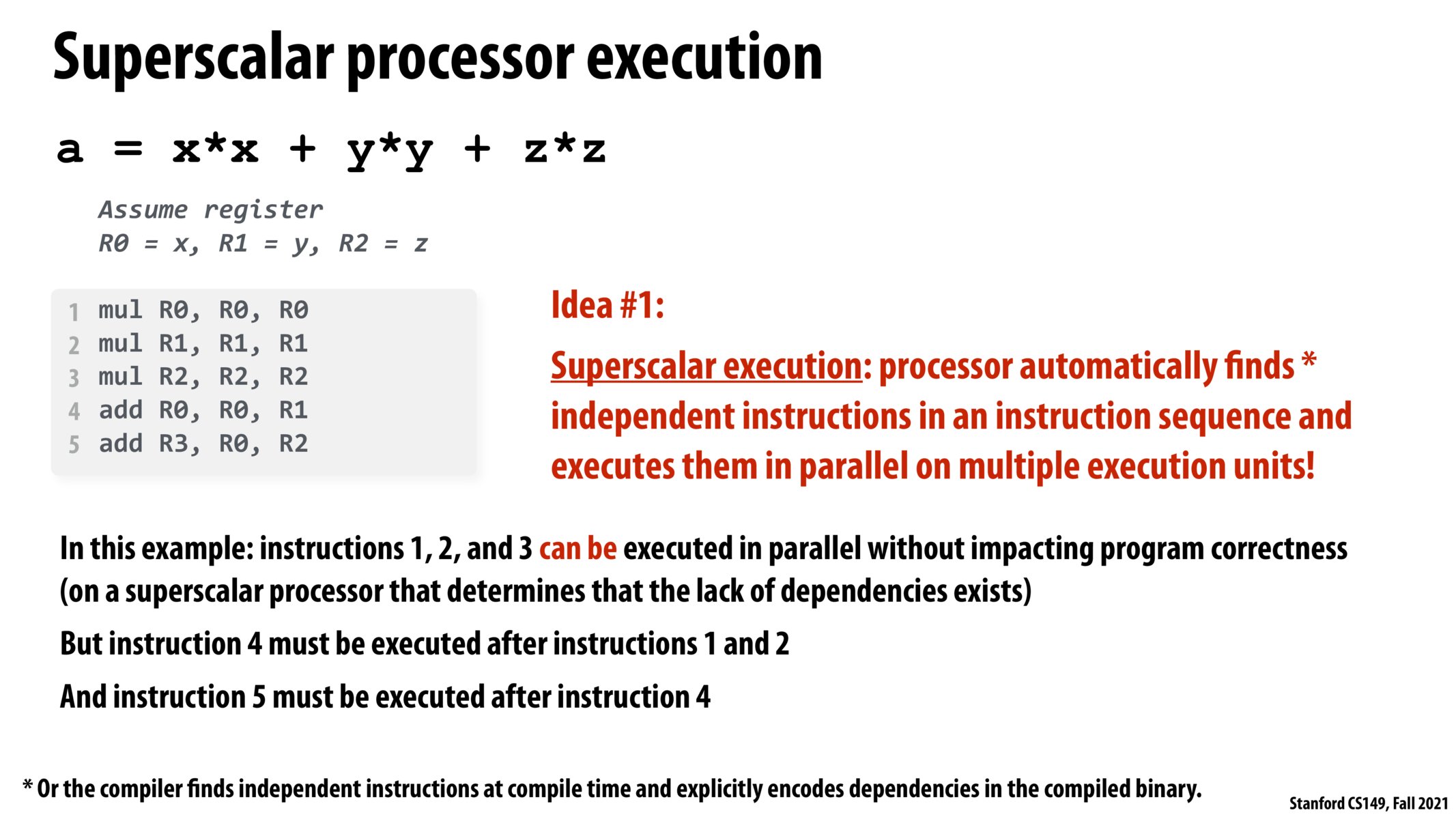

Pranil brings up an interesting point. Typically, jump and execution instructions like add and mul take one clock cycle to execute and a few more to be stored into a register, but data transfer instructions can take a much larger amount of clock cycles depending on what level cache hits or misses. I wonder if its possible to further pipeline and optimize a set of instructions by performing data transfer instructions and jump and execution instructions in parallel on separate cores.

Will we be getting into strategies the processor uses for determining what instructions can be run in parallel and the limitations? I was curious whether there comes a point where doing the actual work of determining what can be run in parallel can take up more time or resources than it's worth.

Is it fair to consider correctness as a requirement for compilers or processors to preserve when trying to parallelize operations? I imagine this is the case but I'm wondering if there are contexts in which speed matters so much that correctness is a tradeoff that we would be willing to make (e.g. this parallelization will give us 1000x increase in speed, so if we have to run it 50 times to get the correct answer, that is still worth it).

What is the overhead cost of automatically finding instructions which can be computed in parallel? I would imagine that in many cases, parallel execution is not possible, so we will be wasting a lot of time seeing whether we can execute instructions in parallel. I would imagine that this algorithm is much more expensive than doing a single multiplication.

@tlisanti, @jtguibas, in EE282 and EE180, there's a lot of discussion about when you can parallelize. As it was briefly discussed in class, it has to do with "dependencies". Specifically, there are hazards such as "read after write" (RAW) and "write after read" (WAR) hazards between instructions.

In short all you need to know for whether instructions conflict with one-another are what registers are being used and whether they're being written to or read from. These checks tends to be much faster than executing arbitrary instructions in the ALU. since there's dedicated hardware to figure out what instructions can be rearranged on the processor. Because of this, it tends to be the case that the cost of figuring out how to rearrange isn't nearly as much as the gain from executing several instructions at once and shaving some clock cycles.

Hope this is mostly correct, and am excited to see what the TA's have to say about this.

@riglesias, I appreciate you expounding upon the tradeoff between overhead from analyzing parallelism potential and actual execution. I'm curious if this is something that is tied most specifically to superscalar execution (or Instruction-Level parallelism at large), or if there's a greater set of principles/empirical observations that reflect this idea: that the analysis to determine conflicts in read/write permissions most often outweighs the benefits to a naive execution of the same program. I'd imagine we'll learn to classify and identify those cases, too, throughout 149 :)

@shreya_ravi I think quantum actually has something vaguely similar to this, where because of the sensitivity of the computer to external noise is so high that state gets corrupted extremely quickly, so correction algorithms need to be run to ensure that state is actually still good (i.e. quantum threshold theorem).

For classical/normal computing, my gut feeling is that it might not be as viable, because in my (admittedly limited) imagination, an incorrectness-permissive execution that guarantees eventual correctness would have to be doing all the same work anyway (do the operation, check the dependencies), except that the order is more fluid. While I can totally see that yielding performance improvements in best-case, where it happens upon a correct dependency path, it's potentially much slower when the dependency chain breaks because there's work that has to be redone. Anyway, take this with a grain of salt; I'm about as far from a microarchitecture specialist as one can get.

@ecb11 Read/write ordering analysis is actually very prominent in task-level parallelism (for ex. in thread-level parallelism), so it's not just limited to ILP, although it's the programmer (usually) that's doing the analysis in that case. For example, memory is a big performance hurdle in modern systems, especially in parallel environments, because moving data in and out of main memory has various complexities, both from a correctness standpoint (i.e. ordering) as well as from a cache performance standpoint, because multiple cores trying to work with the same location in memory causes issues with caching that interfere with performance. So, in view of that, a lot of effort is put into making algorithms more efficient with that sort of analysis.

Please log in to leave a comment.

We discussed here that the minimum number of cycles in which this program can be executed is 3. But I just think that a strong assumption that we have made here (for our simple toy processor) is that all operations (including add and mul) take the same time to complete execution.