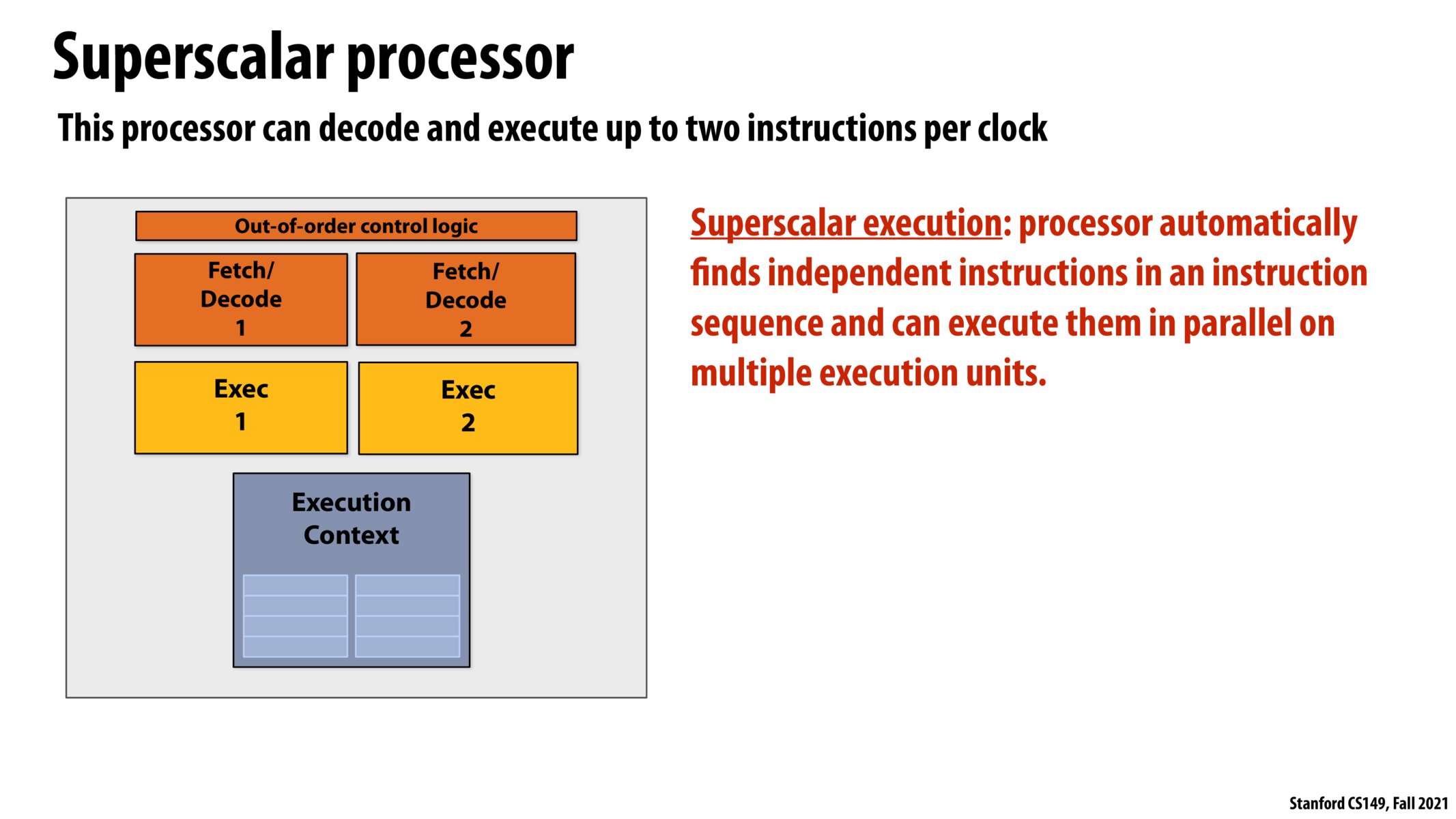

@joshcho In EE180 + EE282, we use the rule of thumb that each of the boxes (fetch/decode /exec) takes one clock cycle. This is relevant because this allows us to work with the individual "stages" in the "5 stage pipeline" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classic_RISC_pipeline) and analyze the effect of "running multiple parts of the pipeline at the same time".

Additionally, it's common practice to use the abstraction "clock" cycle to mean "the slowest part of your pipeline" since otherwise it's difficult to talk about performance improvements in terms of clock cycles (so in your case, if fetch/decode took more than "one cycle" we would likely just make that the time for one clock cycle").

The idea of the 5-stage pipeline is that each part of the pipeline is always or almost always in use (after an initial "warm up" period of fetching /decoding some instructions), so in this case, I'm not sure if there is a benefit of having 5 Fetch /Decode units if there are only 4 ALUs (which Fetch/Decode Unit would feed what into which ALU?).

In class, Prof. Kayvon also mentioned that compiler doesn't generate these out of order instructions for ILP because there are inherent data and execution dependencies in the algorithms that programmers write that are hard to optimize from compilers. However, I would like to ask whether it is possible during the translation from assembly to machine code to also utilize superscalar hardware features because at that phase the translation unit has the knowledge of what target architecture the machine code would run on. Then, there is no need for out of order control logic that is expensive to run.

For instance, the translation unit can build a dependency graph from the assembly and do analysis on the instruction dependency graph to find out potentially parallel instructions to run. Then it can issue a hardware instruction to say these two instructions are parallel and hence please run them on separate execution units.

@gohan2021. To be clear, different processor designs make different choices about what should be done dynamically by hardware at runtime, and what should be done up front by a compiler. For example, a compiler, which definitely can take time to analyze a program, might generate a binary that already explicitly denotes what instructions can be run in parallel. This means that hardware can be simpler. By here are some of the issues:

- A compiler can spend a lot more time analyzing a program, and the results of that analysis can be reused each time the code is run.

- However, if dependencies in a program are dynamic (data dependent), a compiler might need to be conservative, where runtime hardware analysis knows the values in question and might be able to more aggressively optimize.

- If a compiler is tasked with identifying parallel ops for a specific machine, then new hardware architectures might require a recompile for code to be efficient on them. Delegating some optimizations to hardware means that the scheduling algorithms of what instructions to run when can be specialized to the design of the hardware.

@kayvonf makes sense. thanks for the clarification.

Tomasulo algorithm (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomasulo_algorithm) can give a general idea on how hardware determines data & resource dependency and executes instructions out of order.

Please log in to leave a comment.

What is the number of clocks usually associated with fetch/decode? If they take longer than 1 clock, then wouldn't it make sense to have more fetch/decode then execution units?