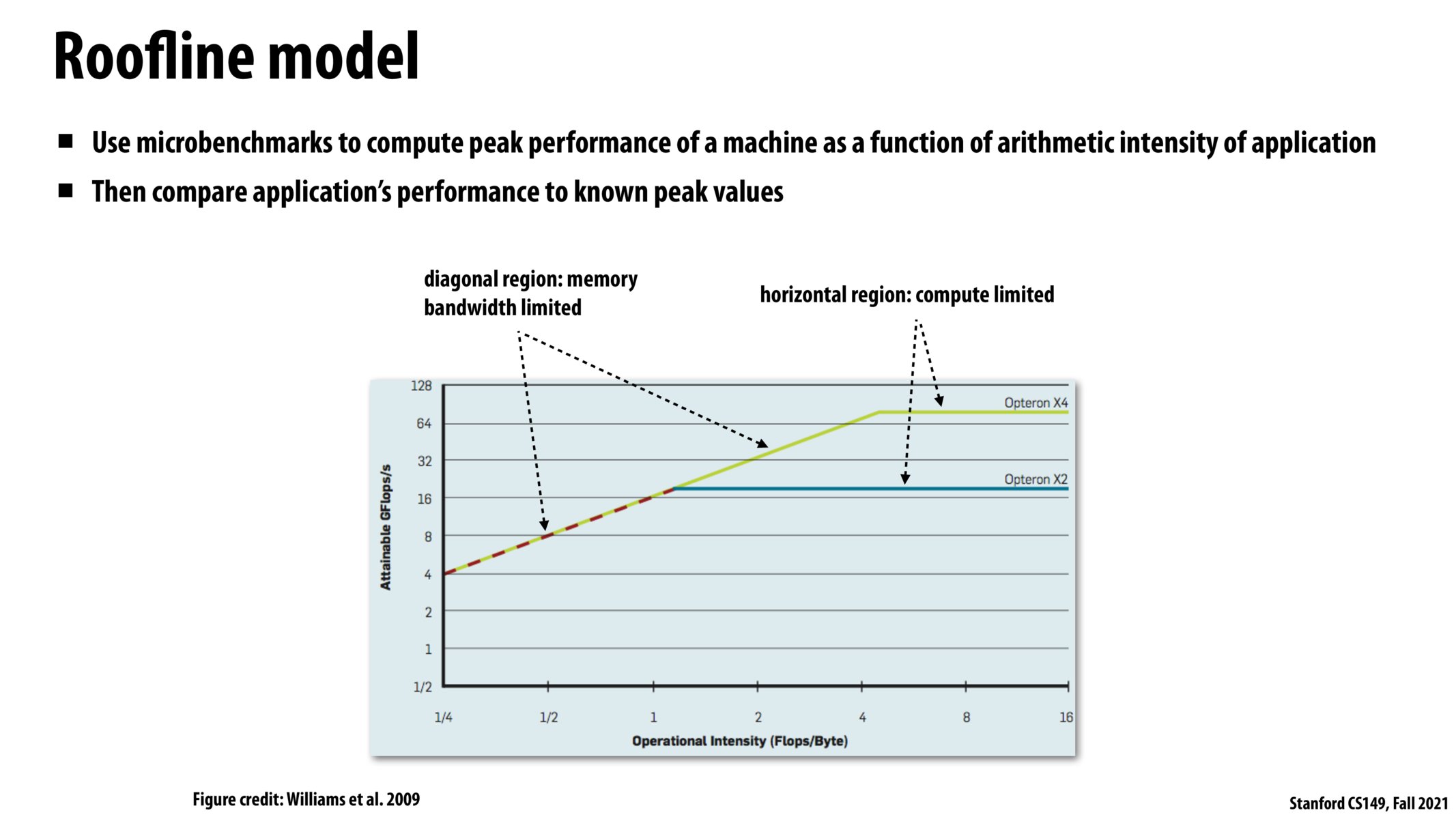

I think the slope of the roofline model at the left of the graph where we are bandwidth bound is the memory bandwidth, measured in gigabytes/second. Algebraically, this is derived from dividing the units of the axes to get (GFlops/s)/(Flops/Byte) = (1Bil Flops/s)*(Byte/Flops) = 1 Bil Bytes / Second = GB/s.

So slope = (y1-y2)/(x1-x2) = (18-4)/(1-1/4) = 14/0.75 = 18.7 GB/sec Bandwidth. And slope is constant for a line. And Bandwidth is a hardware imposed constant number. So it would make sense?

Great job!

This was a really interesting and useful way to understand the regions of computation where programs are either bandwidth or compute limited. One way to think about this is that if increasing operational intensity increases the attainable GFlops/s, the program is bandwidth bound as increasing arithmetic intensity helps reduce the frequency of memory accesses (and can cover gaps due to bandwidth). However, if increasing operational intensity results in no increase in attainable GFlops/s, the program is compute limited as our ability to perform the operations is capped.

I've heard that scaling of memory systems is much slower than compute scaling, does that mean that programs are increasingly becoming bandwidth limited because it is hard increase the operational intensity of a program?

@alanda, I think when they say that memory doesn't scale, they are referring to memory latency, which is limited by the wire delays. On the other hand, as far as I know, memory BW has been growing at a decently high rate.

Please log in to leave a comment.

What is the general strategy for adjusting operational intensity? For a given application this seems pretty domain-specific.